Inizio / Capitolo II: Piranesi nell’architettura e in urbanistica

Conceptual Campo Marzio

Professore di storia e teoria dell'architettura

The Oslo School of Architecture and Design (AHO)

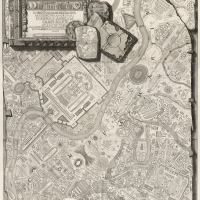

The impact of Piranesi's large plan from Campo Marzio on post-modern and contemporary debates on architecture traces back to an article by Vincenzo Fasolo, professor in architectural history at Rome's Sapienza University, published in 1956. Fasolo argued that archaeology only played a limited part in Piranesi's vision of Rome. Rather, the plan was a testimony to Piranesi's own creative impulse as architect. His inventions were analogous to the forms suggested by antiquity, Fasolo claimed .

If they were analogues, it suggested that Piranesi never truly meant the plan to be a portrayal of ancient Rome at all. So, what is it? Fasolo's conclusion gave room for a conceptual city to exist independent of, or interwoven with, the archaeological city. He pointed out the paradox of Piranesi breaking with history in the same move that he seemingly reconstructs it – a view on history that has intrigued architects ever since, from Louis Kahn to Rem Koolhaas.

The great plan – or “Ichnographia” – from Il Campo Marzio dell'antica Roma (1762) consists of six copper plates that combine in a staggering vision of the northern area of Rome, measuring in total m 1.35 x 1.17 .

© Harvard University Houghton Library.

Today, the map reigns as Piranesi's perhaps most famous image, rivaled only by the imaginary prisons, the Carceri. An intensely imaginative take on ancient Rome, enrolling the remains in sweeping geometric patterns, makes the plan a tour de force in urban theory and a highpoint in the history of the graphic arts. It is extraordinary, therefore, that the map was entirely excluded from consideration in the early literature on Piranesi. Twentieth-century scholars on the artist like Arthur Samuel, Arthur M. Hind, and Henri Focillon entirely failed to take any notice of the plan. Its obvious distortion of archaeological fact, we must take it, proved unsettling to period that approached the past as if history was a natural science.

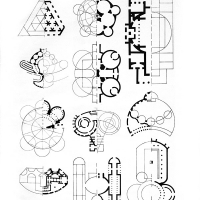

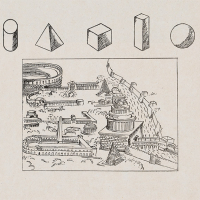

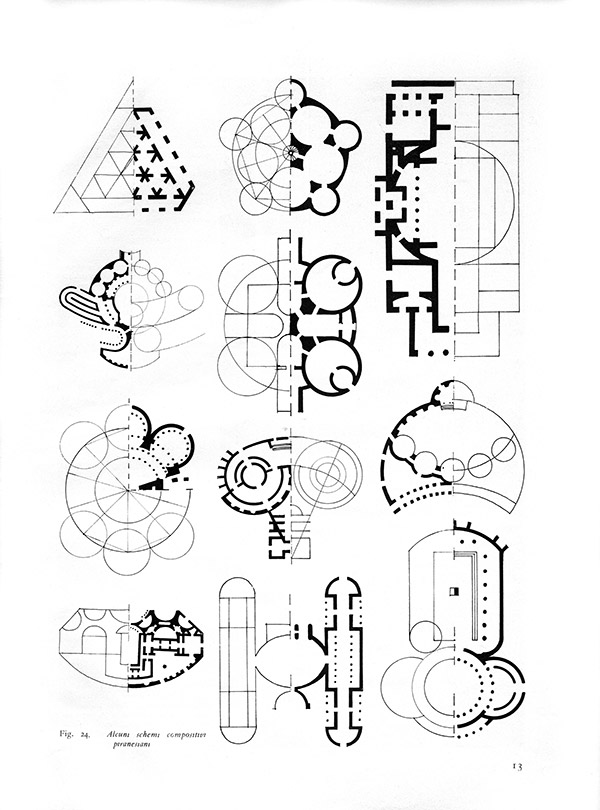

Fasolo solved the dilemma by “peeling” off the erroneous archaeology as a layer obscuring Piranesi's true intent. The richly articulated surface was simply a veil covering what Fasolo identified as essential forms lingering behind or beneath the lacework of architectural detailing. Not taking the archaeology at face value, so to speak, Fasolo resuscitated the map's significance by glimpsing the essential it covered. This rereading of Campo Marzio affirmed an obvious modernist approach that trails back to the early twentieth century. In fact, the very formulation of modernism, which became the dominant style of the twentieth century, rests precisely on the extraction of volumetric forms from printed maps of Rome. In 1915, the Swiss architect Le Corbusier, then known as Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, settled at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris to study old prints. Looking at Pirro Ligorio's reconstructive map of ancient Rome, the Anteiquae Urbis Imago from 1561, Jeanneret distilled from this map's fanciful reconstructions a few basic geometric shapes – a cube, a cone, a pyramid etc, and converted his finds to a diagram first published in the journal L'ésprit Noveau (1920) and later in Le Corbusier's own Vers un architecture (1923). While at the library, Le Corbusier also looked at Piranesi's Campo marzio. In this case, however, he was unable or unwilling to “look through” the plethora of elements like he had done with Ligorio's map. On the contrary, it appeared to consist of “nothing but porticos, colonnades, and obelisks!!! It is crazy. It is horrible, ugly, and idiotic. Make no mistake, it is anything but grandiose” . It was left to Fasolo, to penetrate the ornate surface and fixate the hidden shapes.

Fasolos's analysis somewhat unhinged the Campo marzio plan from time and place. Peeling off one layer of the city, as if it were a mere stylistic veneer, to reveal another, left Piranesi's contribution ambiguous. Piranesi cannot be called the architect of forms that essentially emerged with Fasolo's own method of unveiling. The split vision of Rome exhibited a crack in the reception of the past. For future architects the value of the map lay in its method, not its monuments.

No one did more to enhance the conceptual dimension of Campo marzio than Manfredo Tafuri in the two articles “Per una critica dell’ideologia architettonica” (1969) and “L’architettura come ‘utopia negativa’” (1971), which reappeared edited in Progetto e utopia (1973) and La Sfera e il labirinto (1980) respectively. The plan's archaeological mask fooled no one, he declared. To Tafuri the plan was an experimental design, a monstrous pullulation of form, which signaled Piranesi's revolt against stagnant bourgeois types and institutions. Prefiguring Tafuri's own position, Piranesi as an architect managed to short-circuit “postmodern” recycling of the classical past. The incessant geometric patterning more than simply clashed with the ancient evidence; it displayed the clash itself as the only honest methodological stance that architects, then and now, could take towards the past, according to Tafuri.

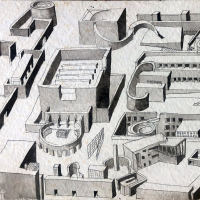

© Steven Holl Architects.

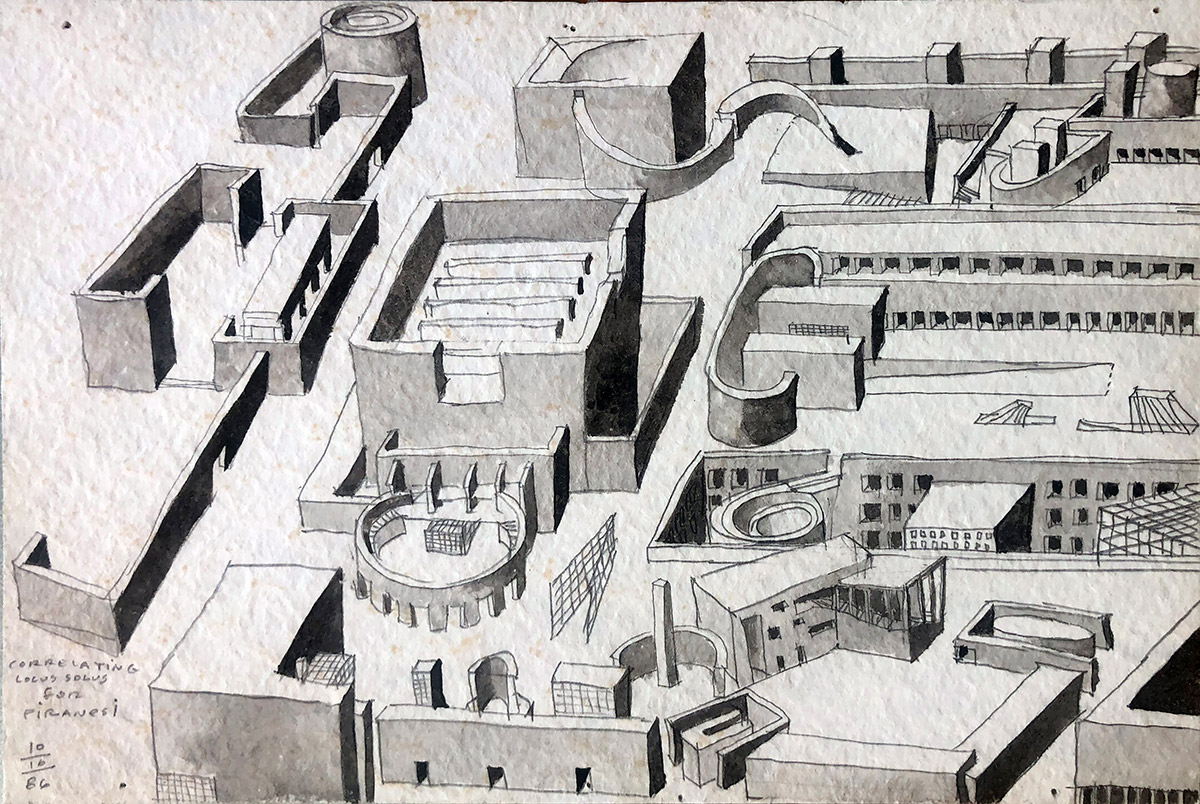

Tafuri's interpretation had a significant impact on American architectural discourse in the 1970s and 80s. His Progetto e utopia was translated into English in 1976 and sold in no less than 21 000 copies over the next two decades . For example, no sooner had Steven Holl arrived in New York as an ambitious young architect than he picked up a copy of Tafuri's book and turned to Campo marzio as a tool to rethink architecture . Peter Eisenman, one of the influential formalists emerging in the 1970s, labeled what he considered his most important work (a proposed square in Venice) a “Tafuri-Piranesian project” and used all his savings on a copy of the Campo marzio plan, which to this day decorates his bedroom wall . “In a single map Piranesi suggested that there was no one scale, no one time, no one location, and no one reality,” he summed up, intrigued by the idea of a city plan unmoored from the historical urbs it pertained to reconstruct . These two, as well as others, were caught by the spell of the post-postmodern rereading of Campo marzio, turning to it as a manual for detaching architectural form from tradition. One could say that the Campo marzio plan became the historical alibi for an architecture that paradoxically attempted to break with history.

© OMA.

Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas has adopted Piranesi's map as an “essential form” in its own right and applied it with a varying degree of consequence. “It really is a code and it is also a code that I have experienced is very efficient in almost any culture – Thai, Chinese, the Italians, the Americans; everyone understands it, even if they don’t know what it is" . In the course of three decades, and spanning projects that comprise libraries and airports, from Paris to Doha, the plan has gradually “sunk” into the design. It has gone from being quoted as a mere décor element to become integral to the conception of buildings as such. In the construction of the National Library in Qatar (2018), for example, the plan was “always on my mind,” Koolhaas admitted, although a direct reference nowhere is obvious. The Campo marzio plan operates from deep within the architectural design much in the same way the set of geometric schemata, identified by Fasolo sixty years earlier, seemingly governed Piranesi's extravagant compounds. In this perspective, the surprising conclusion is that the intensely transgressive Koolhaas simply continues a modernist tradition.

From an image of Rome that appeared so intricate that not even Le Corbusier was able to look through it, Fasolo, then others, extracted nuclei from a basis that was less architectural than methodological. Fasolo's suggestion that the plan contained “invisible” forms undermined the plan's archaeology of course – its curves and colonnades, stairs and statues. Instead of contesting Piranesi's individual solutions, monument by monument, Fasolo seemed to say that the entire archaeological “layer” was dabbed onto forms that in essence were inventions. It is ironic, perhaps, that Fasolo's method of peeling off the archaeological veneer, to arrive at a “hidden” stratum, itself is archaeological. However, what this hidden stratum is, where it originates, and how it works, depends on the one who looks. In the final instance, a conceptual reading of the plan has allowed architects to interact with the past, the ancient as well as the eighteenth-century one, proving how classical Rome also belongs to the avant-garde.

Galleria delle immagini in sezione

Continuare >>>Piranesi attorno a Giovanni Battista Montano: ripercorrere i tracciati per appropriarsi dell'Idea

Riferimenti bibliografici

- Allen, Stanley (1989): “Piranesi’s ‘Campo Marzio’: An Experimental Design,” in Assemblage, 10, pp. 70–109.

- Connors, Joseph (2011): Piranesi and the Campus Martius: The Missing Corso: Topography and Archaeology in Eighteenth-Century Rome, Milano, Jaca Book.

- Duboy, Philippe (1979): “Ch. E. Jeanneret à La Bibliothèque Nationale Paris 1915”, in Architecture-Mouvement-Continuité, 49 (Numéro spécial Le Corbusier), Parigi, pp. 9-12.

- Eisenman, Peter (2007): “Piranesi and the City”, in Sarah E. Lawrence (a cura di), Piranesi as Designer, New York: Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution.

- Fasolo, Vincenzo (1956): “Il Campomarzio di G. B. Piranesi”, in Quaderni dell’Istituto di Storia dell’Architettura, n. 15, Roma.

- Marletta, Angelo (2016): Il Campo Marzio dell'Antica Roma: Giovanni Battista Piranesi e l'arte del contemperare, Ariccia, Ermes.

- Ockman, Joan (1995): “Venice and New York,” in Casabella: International Architectural Review, 59, 619-620 (febbraio 1995), pp. 57-71.